On a summer day, Alina Kusmangaliyeva sat on a phone call with Nicole Sadek (20C), recounting the day she and nearly two dozen classmates suddenly collapsed, foaming at the mouth and convulsing. Kusmangaliyeva is a young woman from the village of Berezovka, and believes, along with other former residents and environmental advocacy groups, that the fainting episodes were the result of years of exposure to toxic emissions from a nearby oil and gas field. These episodes were not a thing of the past: Kusmangaliyeva had fainted as recently as four days before her interview with Sadek in July.

That interview confirmed the story Sadek had traveled across the world to tell. Sadek received the Livingston Award for International Reporting on June 10 for her article, “The Lost Village,” published with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

ICIJ is a global network of journalists who collaborate on cross-border investigations and share reporting with media outlets worldwide. The Livingston Awards for Young Journalists, presented annually by the University of Michigan’s Wallace House Center for Journalists, honors outstanding journalism by reporters under 35 years old. Sadek’s piece exposed the displacement and health consequences that residents faced in Berezovka, a village located near a massive Karachaganak oil field jointly operated by Western energy giants.

Though her trip to Berezovka was her first foreign reporting trip, Sadek was no stranger to the field of investigative journalism.

Georgia News Lab, a now-defunct investigative reporting partnership between college students and Georgia newsrooms, gave Sadek her first taste of investigative work with outlets like the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Georgia Public Broadcasting during her final year at Emory. Even before this program, Sadek had already begun cultivating her interest in journalism through campus clubs.

“I always knew I wanted to be a writer,” Sadek said. “But it wasn't until the Wheel that I started considering journalism.”

As an undergraduate student, Sadek served as social media editor, copy editor, editor-at-large and eventually co-editor-in-chief of The Emory Wheel. Each position offered her new angles on storytelling.

“I had an opportunity to jump around and write where I was interested in,” Sadek said. “That gave me a taste of a whole bunch of different styles of writing.”

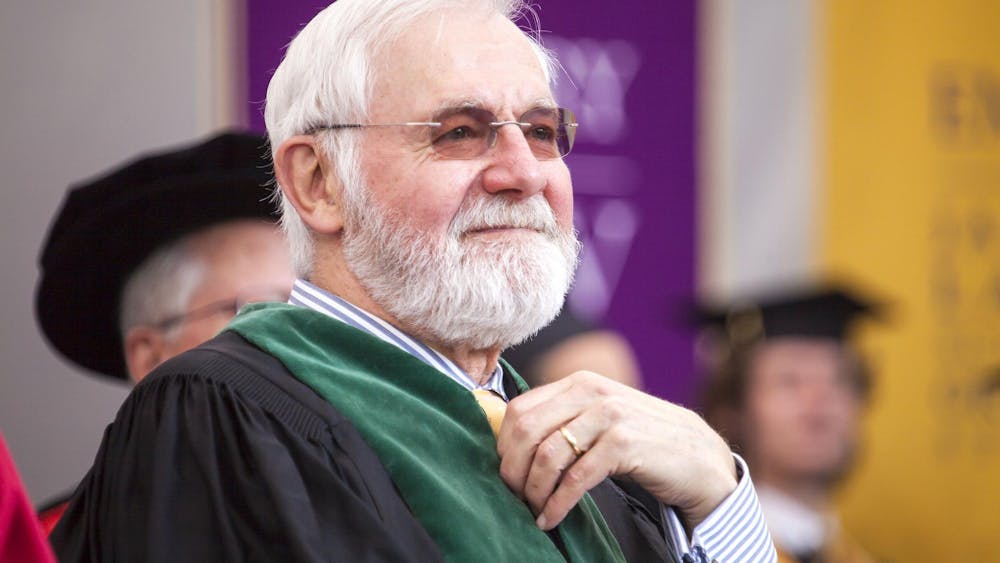

In a media ethics course with Professor of Practice in Emory's Creative Writing Program Hank Klibanoff, Sadek furthered her commitment to journalism.

“The ethics class was really, really helpful because it was the first time I even understood the ethical dilemmas that can come up in journalism,” Sadek said. “In my early career, I have already faced things of that nature.”

Klibanoff’s course prepared Sadek to face similar difficult media ethics decisions at ICIJ, such as procuring anonymity for sources.

One of Sadek’s recent projects, “China Targets,” investigated how the Chinese government works to repress dissidents both inside and beyond its borders.

“A lot of those people were understandably nervous to speak out because of the threats from the Chinese government,” Sadek said. “We often have to deal with, is this person facing an imminent threat? And if they are, should we keep them anonymous?”

After graduating from Emory with degrees in International Studies and English and Creative Writing, Sadek headed to Arizona State University to pursue a master’s degree in investigative journalism.

Following her studies at ASU, Sadek began a fellowship at ICIJ, where she now works as an investigative reporter. Her work at ICIJ has included major international investigations such as “The Uber Files,” a collection of articles drawing from a leak of over 129,000 documents to reveal Uber’s tactics to influence U.S. politicians, evade regulations and expand globally through questionable practices. In another story, Sadek and other ICIJ journalists traced looted Cambodian artifacts to a billionaire’s Florida mansion, which they accomplished using online photos and archival research.

Sadek is drawn to the long-form, research-heavy nature of investigative journalism.

“There's a lot of reading, reading other journalism that's been done on that topic, speaking with experts on that topic before I even find what angle I want to pursue,”Sadek said.

Sadek joined ICIJ’s “Caspian Cabals” project, which investigated how Western oil companies secured access to the lucrative Caspian pipeline network despite widespread corruption. Sharing the broader story about these companies’ involvement in Kazakhstan was already underway. However, Sadek was eager to find a human-centered perspective through which to tell it.

The ICIJ team was seeking a story that highlighted the impact of oil development on local communities. That was when the team learned of Berezovka, a small village whose residents relocated in 2014 because of concerns over toxic emissions from the nearby oil and gas field. Despite the time that had passed since Berezovka residents’ relocation, Sadek was intent on finding evidence of the present-day consequences.

“We knew we didn't want to do a story if it was entirely historical, we needed to find something that was current,” Sadek said. “And for a long time during the reporting, we couldn't find it.”

That changed when Sadek met Kusmangaliyeva, one of the affected residents willing to share her story.

Throughout the months Saddek spent researching, she faced many hurdles: language barriers, limited local media coverage and gaining the trust of a community that had been traumatized, relocated and largely forgotten. She leaned on local partners from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, who had already built trust in the region. A non-governmental organization working with the villagers had also preserved crucial documentation, like health surveys, letters and agreements, that laid the foundation for her investigation.

Sadek’s article, “The Lost Village”, which was published in November 2024, painted a portrait of Berezovka’s transformation from a self-sufficient village, where families raised animals and grew vegetables, to a shuttered community whose residents were eventually relocated after years of illness and uncertainty.

Sadek explained that stories similar to Berezovka’s typically drive change by raising global awareness rather than directly prompting government investigations or causing corporate consequences.

“It's a bit idealistic to hope that these oil companies would change anything,” Sadek said. “So there hasn't been that tangible impact the way there was for the Cambodian statues being repatriated. But I do think that people becoming more aware of this story is a pretty great result of the story.”

The Livingston award, Sadek believes, will help bring this piece to a broader audience. With the award under her belt, Sadek is already looking toward her next story, hoping to continue weaving narrative storytelling into her future work.

Sadek’s advice for aspiring journalists applies to those pursuing any profession — she urges students to embrace collaboration, double-check everything and welcome feedback.

“I would say if you want to do journalism, you need to read a lot of journalism,” Sadek said. “I would also say double check everything. Do not give yourself room for someone to discredit you, which I think today is happening a lot more than it used to.”

Correction (8/23/2025 at 8:25 p.m.): A previous version of the article stated that Nicole Sadek (20C) met with Alina Kusmangaliyeva in Kazakhstan. This is incorrect, Sadek and Kusmangaliyeva met over the phone. The article has been updated to reflect this.