Every Thursday, you can find members of the Emory University Buddhist Club gathering for an hour of meditation in Cannon Chapel. During this respite, attendees practice mindfulness, listening to their head and heart and stepping away from the chaos of college life.

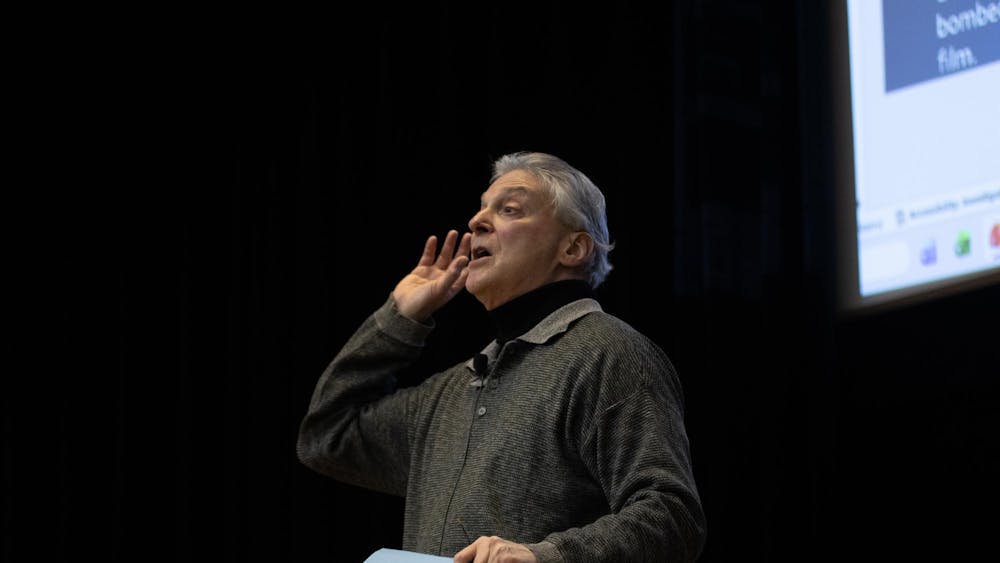

On Oct. 30, however, the Buddhist Club’s meeting was noticeably different: After the Venerable Priya Rakkhit Sraman, the Buddhist chaplain of Emory, led a brief meditation session, Tibetan monk Jampa Thakchoe and Associate Teaching Professor of Psychology and Director of Undergraduate Research Andrew Kazama (06G, 10G) gave a talk on the connection between neuroscience and meditation. Thakchoe also discussed tukdum, a meditative state in Tibetan Buddhism that people can enter after clinical death.

Buddhist Club co-President Kio Whitten (26C) explained her personal connection to tukdum, sharing how important it was to them to make this event as accessible as possible. They met Thakchoe and Kazama while visiting India last summer as part of the Emory Tibetan Mind/Body Sciences Summer Abroad program, where Whitten first learnt about the concept of thukdum.

“I learned about tukdum there,” Whitten said. “And we were constantly going over the connection to neuroscience and meditation.”

Thakchoe discussed a clinical study in which researchers collected data over a 30-year period from individuals who reached tukdum, finding the human body takes longer to chemically decompose while in the meditative state as compared to an average human. He hypothesized that the end of biological function does not mean the termination of human consciousness.

Speaking after Thakcoe, Kazama emphasized the importance of connecting science and religion. He explained how tukdum relates to the average person, highlighting to attendees that meditation can lead to an increase in self-awareness.

“In terms of emotion regulation, one of the reasons why mindfulness meditation is so helpful is because it allows us to cut out all of the extra anxiety that's happening in the past and in the future,” Kazama said.

After the event, attendee Elise Smith-Davids (26C) reflected on the discussion and expressed her enthusiasm to learn more about the application of Buddhism to modern science.

“Meditation is actually extremely neurologically helpful,” Smith-Davids said. “It calms the nervous system, and it's also a good reset button and probably more common than you would expect.”

The Emory Buddhist Club hosts various interdisciplinary events throughout the year, focusing on environmentalism, education and science. Buddhist Club co-President Samali Wijetunga (26C) noted that this event had a larger reach than usual, with around 50 attendees.

“We try to bring those cultural and religious events to the club, because not everyone here is Buddhist,” Wijetunga said. “But a lot of people like to learn, either just out of curiosity or out of being Buddhist themselves.”

In the future, Whitten hopes to expand the scope of the club’s offerings to the wider Emory community and bring together more people with unique backgrounds.

As people filtered out of Cannon Chapel after the event, many possessed a newfound sense of awareness. When life becomes chaotic, the notion that spirituality can be biologically connected to humans brings a sense of peace and allows for introspection into something greater than yourself.

“I was thankfully able to put together this event,” Whitten said. "I definitely wanted to make it open to as many people as possible, not even just our like Buddhist community.”

Like Whitten hopes, attendees left the event with knowledge that may help bring forth a future filled with mindfulness and excitement, combining disciplines like neuroscience with religion to better understand our community, world and themselves.