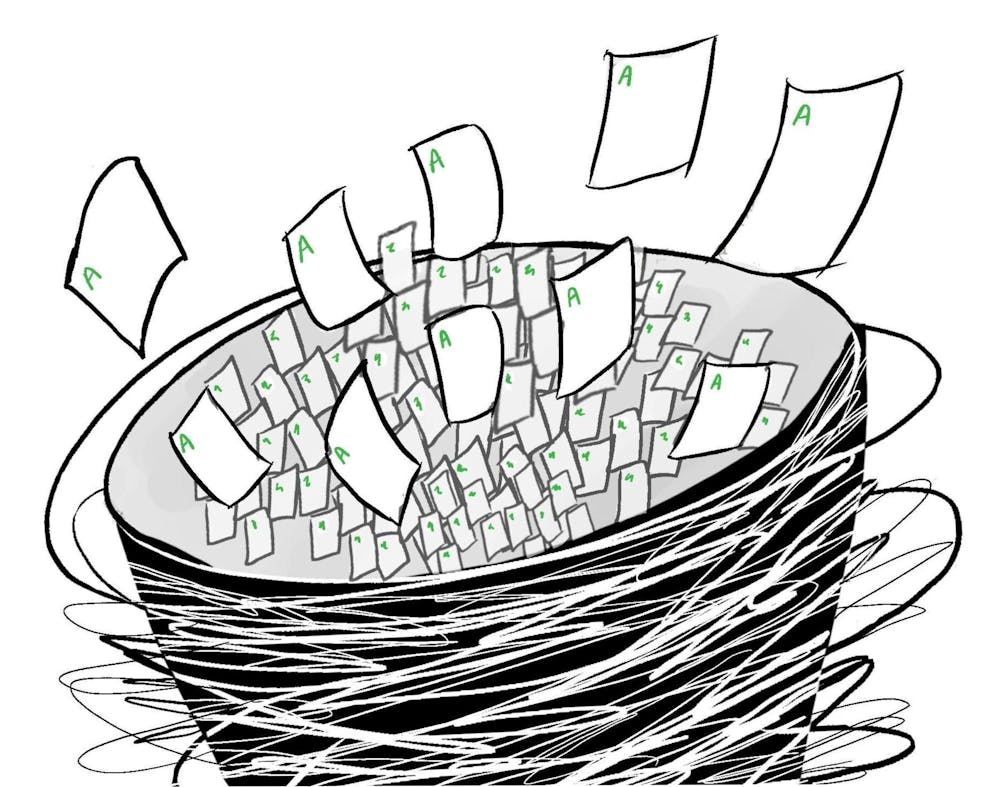

This spring, when the Class of 2025 walked across the commencement stage, over 72% of them had a GPA over 3.5. 20 years ago, only 41.5% of the class of 2005 had a GPA of over 3.5, and this percentage stayed below 50% through the class of 2017. Additionally, the Class of 2025 had an average GPA of 3.68, higher than any average GPA in the last 20 years.

In the last five years, the average ECAS graduate’s cumulative GPA has risen from 3.48 to 3.68. This increase is double the average GPA increase from 2005 to 2019, during which GPAs rose from an average of 3.33 to 3.43.

Former Emory University School of Medicine Professor Dr. Michael Lubin, a critic of grade inflation for over a decade, criticized the increasing concentration of grades above a 3.5 and called into question what Emory students’ grades actually mean.

“Grades don’t mean anything,” Lubin said.

While students may view receiving higher grades than students from previous years positively, Associate Professor of Political Science and former Emory College Faculty Senate President B. Pablo Montagnes said that grade inflation can result in worse outcomes for students.

“You end up in a bad equilibrium of low effort, high grades, and that’s ultimately bad for students, because they’re going to learn less, particularly in classes where repeated hard work is necessary to consolidate the skills,” Montagnes said.

Additionally, Associate Teaching Professor of Physics Tom Bing, who chairs the ECAS Faculty Senate’s Curriculum, Assessment and Educational Policy Committee, pointed out that graduating students’ career opportunities may be hurt, as employers may not value a high GPA from Emory due to grade inflation.

“What does it even mean to graduate from Emory with a good GPA?” Bing said. “If everybody out there in the medical schools and the law schools, and even the working community, sees a great Emory GPA, and it doesn’t mean anything like, ‘Oh well, everybody from Emory has a great GPA.’ That dilutes the value of it.”

Possibilities for policy changes

Montagnes said that changes in the grading policy would have to come from an agreement by the ECAS faculty. The Emory College Faculty Senate can propose curriculum policies that ECAS faculty can vote on for approval. Previously, the body introduced new General Education Requirements before the ECAS faculty voted to approve them. Montagnes added that ECAS Dean Barbara Krauthamer could not unilaterally implement changes to college grading practices.

According to Montagnes, ECAS faculty members could create a policy similar to that of the Goizueta Business School, establishing a standard grade distribution where grades are based on a distribution curve rather than a system where professors can assign students any grade, regardless of their performance relative to the class.

Despite being concerned by the rise in GPAs at Emory, Professor of English James Morey said that he would not be in favor of instituting a mandated curve, saying that grades “cannot be legislated.”

“No one tells me what grades to assign,” Morey said. “That is a faculty privilege, one of the few things faculty can still do and control.”

Krauthamer wrote in a statement to The Emory Wheel that she is confident that faculty are responsible when grading students.

“Our faculty enjoy the academic freedom to fairly assess student work and progress in their classes,” Krauthamer wrote. “I’m confident that the faculty in Emory College take that responsibility seriously.”

Like Morey, Bing said he is not a fan of a mandated grade distribution curve and would prefer if ECAS leadership gave professors more information about how their grading compares to other professors.

“Data is never a bad thing,” Bing said. “All I would want is that each individual faculty makes a more informed, explicit decision when they’re thinking about their grades.”

Conversely, Montagnes said that giving professors more data may lead to higher grade inflation.

“If faculty become aware that they’re the hard grader, they might say, ‘Oh, maybe I’m out of line’ and become the easy grader,” Montagnes said. “They might also maybe rightly understand that their low grades are hurting students, and so they might change their behavior.”

Alternative perspectives on grading

While many professors may see rising GPAs at Emory as a problem, Professor of Practice in the Department of French and Italian Christine Ristaino and Emory Writing Program Associate Teaching Professor Vani Kannan take a different approach. Both Ristain and Kannan see grading as “punitive.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kannan championed an “A for All” policy, advocating for an approach to grading that did not compare students but was based on the amount of work students put into the class. Additionally, Kannan said in her classes, she creates final projects based on work that is relevant to their interests.

Similarly, Ristaino explained that students have different learning styles and that she believes grades should be based on personal improvement rather than class performance.

“There are a whole bunch of students who are overlooked in general in the school system,” Ristaino said. “My thoughts about grading are that grading is punitive. It punishes the people who don’t do well, who don’t test well or do worksheets well. They could be incredibly intelligent, creative, out-of-the-box thinkers, but they’re punished because they’re not fitting into a particular box.”

COVID-19 effect on grade inflation

At Emory, grades began to significantly increase during the direct aftermath of COVID-19. Montagnes said that this rise was seen across the country.

Bing added to this, stating that it was harder to grade and test “in a rigorous way” while students were taking classes online. Since 2020, the average GPA has increased by 0.2, 200% more than from 2005 to 2019. Adding to this, Morey said it was difficult to give students worse grades due to the extenuating circumstances the pandemic caused.

“How can I possibly penalize any student for what may be a nonsuperlative achievement when the conditions are so difficult?” Morey said. “That‘s basically why the grades went through the roof during the pandemic.”

Montagnes said that while grades were increasing slightly leading up to 2019, this could somewhat be attributed to an increase in Emory’s selectivity.

“But the fast COVID era rise is not consistent with the school becoming appreciatively more selective over that period,” Montagnes said.

Kannan said that her views toward an “A for All” strategy of grading changed during the pandemic as she realized that students had responsibilities outside the classroom that could affect their learning.

“We had a number of spirited debates around how to assess student work in a context where some of our students were taking care of children full time, some were working full time, some had family members who were sick with COVID, others were sick with COVID themselves,” Kannan said.

While there have been no comprehensive studies published on grade inflation since the pandemic, researchers have found multiple institutions of higher education to have high levels of grade inflation since the pandemic. For example, the University of Oregon and Duke University (N.C.) both saw jumps in GPA in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic.

Other causes for grade inflation

Despite ECAS faculty members’ ability to combat grade inflation, Montagnes said implementing grade controls would be difficult.

“It’s not beyond the realm of possibility that the College could impose a curve of sorts as well, but it would require faculty agreeing to that … that would be, in my opinion, hard to get faculty agreement on, partly because some faculty benefit from the lenient grading,” Montagnes said.

Bing said that grade inflation is partly caused by the incentive structure for professors, making it easier to award “a few extra A’s in one semester.”

Similarly, Morey and Associate Professor of Film and Media Jennifer Porst both spoke about how professors do not want to receive poor evaluations from students and that one way to receive better evaluations is to give out higher grades than students may deserve.

“Student evaluations are a big part of how we are evaluated on a year-to-year basis,” Porst said. “Our salaries depend in part on it. Our promotion depends in part on it, and so it’s a difficult system. When faculty are put in a position of, ‘If I give the grades that I think students actually have earned, if they’re unhappy, it punishes me.’”

Morey and Porst also mentioned how student expectations have led professors to give out higher grades as well. Porst explained that she believes students at schools like Emory expect to receive high grades.

“Because they have gotten good grades throughout their academic career until they get to Emory, their expectation is that they will continue to do so, and sometimes, not all the time, you get students for whom their self-worth is tied up in their grades,” Porst said.

Additionally, Morey said that the high costs of schools like Emory have led to students expecting higher grades.

“The sacrifices that students and their families have to make to just get through a degree program at a school like Emory,” Morey said. “It is hard to think, ‘How much did I pay for this and what? How much did I sacrifice, and I am not being rewarded as I think I should be for future purposes, med school, law school, graduate school, jobs.’ Those are very important questions that should not be ignored.”

Despite the expense of an Emory degree, Morey said that faculty must work on adjusting student expectations to where students understand that a B is a good grade.

Lubin stated that grade inflation is an outgrowth of a culture where everyone expects to be rewarded no matter what. He added that the high GPAs at Emory are “ridiculous.”

“The problem we have in the world is you’re not allowed to make value judgments,” Lubin said.

Montagnes added that since grade inflation at Emory is so high, giving a student an A- or B+ could seem like a punishment.

“You’re going to dramatically affect their place in class rank, their GPA,” Montagnes said. “Then they’re, in some sense, causing harm to those students. As GPA gets really, really high, faculty become more and more resistant to ‘hurting’ a student by giving them a low GPA or low grade in the class.”

Morey stated that Emory should have a mechanism for rewarding “truly exceptional” students. Porst added that she sees the practice of giving out high grades to many students as harming students who do outstanding work.

Spencer Friedland (26C) is the Editor-in-Chief of The Emory Wheel. He is double majoring in Philosophy and Film. Outside of the Wheel he is a member of Emory's Honor Council and Franklin Fellowship. After college he is planning on attending law school.