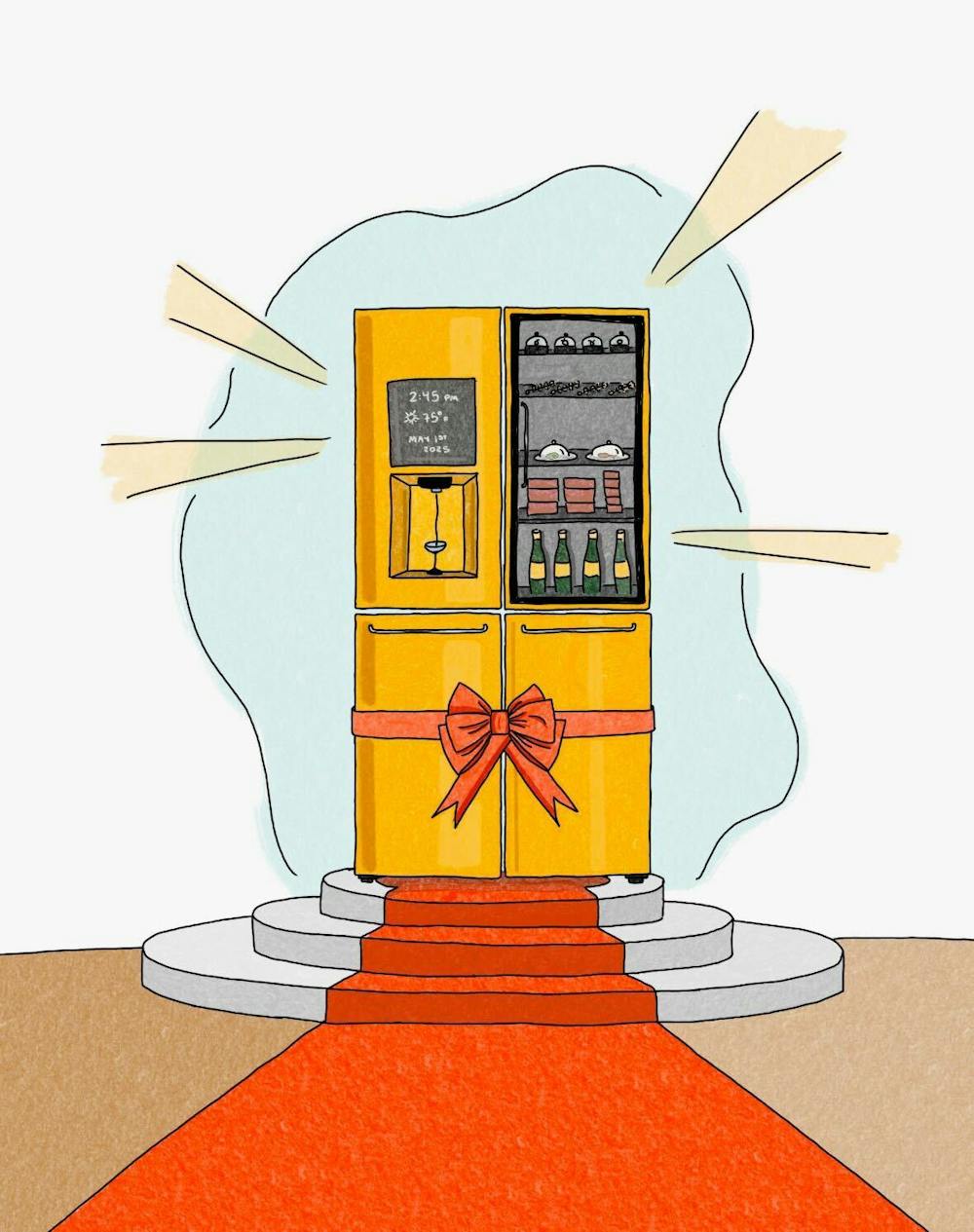

From $19 strawberries to designer grocery bags, a new lifestyle trend is emerging that focuses on the glamorization of food. Fresh kale and homegrown heirloom tomatoes have replaced designer handbags, shoes and cars as the new coveted symbols of status. Social media viewers now fixate on influencers who fill their grocery carts with artisan olive oil and aspire to buy luxury smoothies instead of designer clothes. Amid this flashy rise in food trends, a dystopian divide is growing as individuals with empty fridges consume content of abundant tablescapes. Glamorized health food choices exacerbate feelings of guilt and shame amongst a population facing increased food insecurity. When groceries symbolize status, fleeting trends overshadow individuals’ health and wellness.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when economic uncertainty reached unprecedented heights, people became increasingly fascinated with food, as shown by social media trends. Everyone seemed to be experimenting with a sourdough starter to make homemade bread or exploring their passion for baking as they searched for small joys and enrichment within the confines of their homes. However, the pandemic also saw a disturbing increase in the percentage of U.S. households experiencing food insecurity. Food in abundance, curated and carefully documented by influencers across social media, became an unachievable aspiration for a portion of the working class.

Following the exacerbated economic uncertainty in the wake of the 2024 presidential election and U.S. President Donald Trump’s fiscal policies, the prevalence of food in the lives of ordinary Americans as a status symbol has only increased. Food choices have become a means to elevate the mundane in the face of an increasingly hostile and volatile economy. A 2023 study conducted by Ernst & Young found that over 50% of Generation Z are “extremely worried about not having enough money” to meet their basic needs. Despite this, a 2023 survey conducted by Vogue Business indicated that over half of 166 16- to 24-year-old readers of Teen Vogue, Glamour and Allure in the United States had bought what they considered a luxury food or drink in the last year. Even as economic conditions worsen, younger Americans still will splurge to have the same artisanal farmers market products and abundant fresh produce as the influencers whose social media content floods their screens.

These luxury food item aspirations come as no surprise, considering how several high-fashion campaigns have recently centered around healthy, organic foods. Longchamp’s 2025 Spring-Summer collection interweaves motifs of fresh baked bread and natural picnics with their designer bags. And, thanks to a recent collaboration between Balenciaga and the exorbitantly priced health-focused grocery store Erewhon, consumers can buy $550 aprons and $2,000 brown grocery bags. This collaboration represents a growing ethos of big-name grocery stores, where the luxurious lifestyle that the name of these stores epitomize is the sole driving factor in influencing where people shop and what they buy. The impact of branded food stores, specifically those focused on health and artisanal products, may even influence where people choose to live. A 2017 study conducted by Zillow indicated that the value of homes with a Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s nearby appreciated faster than the typical home in the city.

The use of food as a declaration of social status is also apparent in the Emory University community. Students who can afford to often shun the Dobbs Common Table (DCT), in favor of food trucks and elaborate salad bowls for lunch. The differences between these choices exemplifies the income disparity within the Emory student population, where 15% of the students come from families with incomes in the top 1% of U.S. earners while 6% come from families with incomes in the bottom 20%, as of 2017.

The DCT is pricey itself, costing first-year students upwards of $4,000 per semester. With such an expensive on-campus dining plan, many college students cannot justify additional expenditures on external food options. Not every student has the privilege of buying endless iced coffees from Kaldi’s Coffee and $20 food truck lunches, yet we, as Generation Z consumers, are told that we must aspire for a healthy, organic food lifestyle, regardless of our socioeconomic backgrounds.

By glamorizing expensive and luxury foods, cheaper food options have become associated with shame. A less expensive option at a grocery store does not align with the desirable lifestyle of the $19 strawberry or $40 sea moss, the “next superfood.” By normalizing the overconsumption of luxury food items, we have opened the floodgates for the comparison and exacerbation of pre-existing inequalities over something fundamentally essential for our survival. If having an abundance of food is normal, by logical extent, lacking this abundance implies something abnormal, leading to feelings of guilt and shame among those who cannot afford this lifestyle that social media glamorizes.

The commercialization of nutrition and food, through the latest marketable snack and dietary trend, does more harm than good to public health. Marketing health as a predefined set of superfoods and supplements allows companies to drive up prices of smaller, pre-packaged food units, which are easier to upcharge customers for, treating wellbeing and health as mass sales tactics. Additionally, the widespread marketing of healthy eating regimens and trendy superfoods by influencers detracts from an individual’s ability to explore and determine which food habits work best for maintaining their health. Health, as a whole, differs enormously from person to person. Therefore, individuals must define healthy behaviors themselves through self-selected forms of movements and mindful eating, rather than outsourcing to prescribed regimens. Health and wellness are holistic, and in order to treat them as such, we have to look beyond what the latest social status-determining food fad signifies to society and consider what health means for ourselves.

Contact Antara Gopalan at antara.gopalan@emory.edu

Antara Goplan (28C) is from Walton-on-Thames, England.