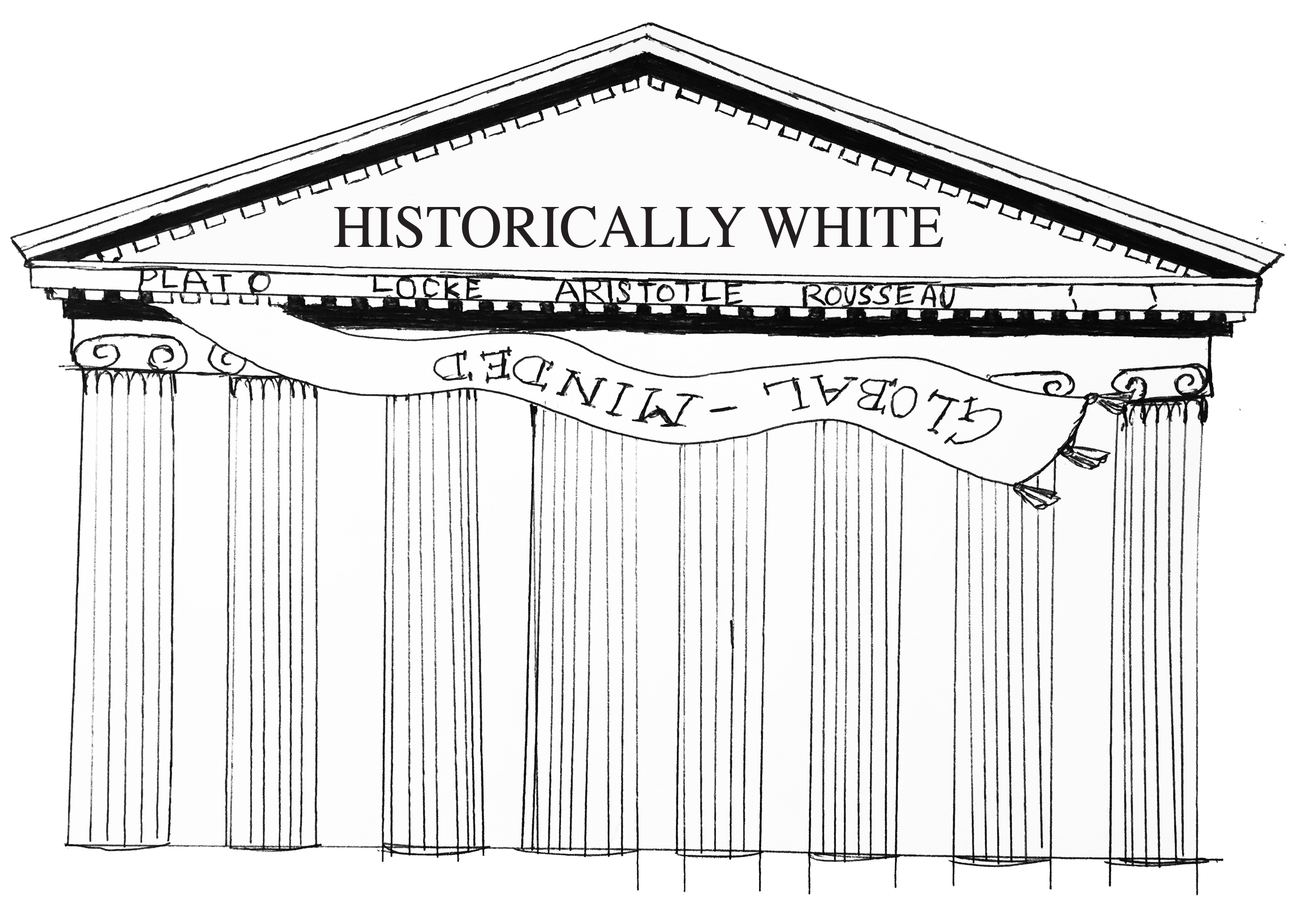

Illustration by Aarti Dureja

The Supreme Court decided on Oct. 6 not to review lower court decisions striking down same-sex marriage bans in five states. This is a watershed moment for the marriage equality movement. On Monday, the Court issued seven curt one-line statements that sent the cases back to the lower courts, all of which approved same-sex marriage.

This event is eerily similar to a 1972 case where the legal battle for same-sex marriage began. That year, the Court issued a similarly brusque summary dismissal of an appeal from the Minnesota Supreme Court called Baker v. Nelson. In it, they declined to hear an appeal from a gay couple wishing to marry, “for want of a substantial federal question.” Unlike today, the Court’s refusal to hear the Baker appeal would have a profoundly negative impact on the legal landscape regarding LGBT rights for decades.

The legal environment today is extremely different. Since Baker, the Court has issued three landmark decisions regarding LGBT rights and over 40 lower court decisions have nearly unanimously found a constitutional right to same-sex marriage. Unlike in 1972, however, and despite the mixed feelings expressed by many marriage equality supporters, today’s one-line orders by the Court are an unprecedented step forward for the cause of same-sex marriage in the United States. It is also the right decision.

The Court of the United States is unique from all other federal courts in that they get sole discretion to choose which cases they wish to hear. It takes four justices out of nine in order to grant certiorari and hear a case. Despite the rabid reactions from the extreme right-wingers, Monday’s denial of certiorari was an exemplary case of judicial restraint.

Every circuit court that has weighed in on the issue has arrived on the side of marriage equality. The decisions from the Fourth, Seventh and 10th Circuit that were before the Court had all struck down their respective bans, as did a Ninth Circuit decision released one day later. Additionally, every state in the First, Second and Third Circuit have legalized same-sex marriage, negating their need to enter the debate.

Because of this unanimity among the lower courts, there is currently no legal conflict that the Court needs to resolve. From the Court’s perspective, it is better to let these cases percolate among the lower courts for now, rather than wade into a potentially explosive social issue.

Controversial social issues are something the Court should tread carefully on in order to avoid the kind of public backlash that occurred after Citizens United (campaign finance laws) or Roe v. Wade (abortion). Supreme Court Justice Ruth Ginsburg has in the past indicated that Roe may have pushed the legal boundaries too far and too fast to the detriment of the pro-choice movement. Learning from this, Ginsburg said last month that she feels content to simply let the lower courts figure out for themselves the same-sex marriage question, for now.

What the Court’s refusal to review these cases means is that every state whose same-sex marriage ban was directly struck down by the lower circuit courts are immediately enjoined from enforcing the ban. In addition, every state that is located within the jurisdictions of the four circuit courts will soon have their same-sex marriage bans overturned as well, after some procedural hurdles.

To see how unprecedented this is, only two years ago, just six states and the District of Columbia legalized same-sex marriage. By this past Sunday, that number had risen to 19. But with the Court’s action on Monday, that number has immediately jumped to 26, and within a few weeks, it will be 35 states.

The meteoric rise of acceptance of same-sex marriage is nothing short of astounding. After what happened on Monday, nationwide marriage equality is absolutely inevitable. Now is the time for patience. I understand that gay couples living in states that aren’t covered by Monday’s action, including Georgia, are still living without legal recognition of their relationship and the benefits that come with such recognition.

I can feel that impatience of wanting those legal benefits that are deservedly theirs. But we must be patient and let the Court conduct its business. It may seem slow, but the end is clear, and nationwide acceptance of same-sex marriage may likely happen within a year.

In a way, everything has gone full circle. What began with a short dismissal in 1972 has ended now with a short dismissal in 2014. With its action, the Court has quietly given the national push for marriage equality an air of momentum and legal legitimacy (not that it didn’t already have that).

For marriage equality supporters disappointed that the Court did not decide to end the discussion once and for all and establish a constitutional right to same-sex marriage nationwide, upcoming decisions in the Fifth, Sixth and 11th Circuit within the next several months may cause the conflict that the Supreme Court is looking for. If so, the eventual outcome would still be the same as if the Court decided to review one of the cases it denied: a Supreme Court decision next June.

It is also possible that the circuit courts may all come down on the side of marriage equality. That way, the Supreme Court may never have to wade into the issue. In a sign of how accepted same-sex marriage has become in American society, how ironic would it be that this decade-long struggle for marriage equality would conclude so quickly with a series of short, one-line procedural orders? There would be nothing better than the Court basically insinuating that same-sex marriage is such a fundamental right that they only needed one line in order to enforce it. For a civil rights movement, this is nothing short of miraculous!

I understand that the courts can sometimes be arduously slow. But the United States has a rich constitutional tradition, and while letting this tradition play out may feel like an unjust delay of fundamental rights, the courts do have a tendency to eventually end up on the right side of history, as they did in Brown v. Board of Education (segregation), Lawrence v. Texas (gay rights) and Frontiero v. Richardson (gender equality), among others. With the Supreme Court’s non-decision last Monday, the marriage equality movement is nearing its victory.

– By Edmund Xu, a College senior from Los Altos, California.

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.