Thirty four years ago on a snowy morning in March, an estimated 1,200 college students crowded in front of the administration building at the University of Pennsylvania. Students were protesting a University proposal that would raise tuition and eliminate several sports programs and the professional theatre program, according to a 1998 article in The Pennsylvania Gazette.

When the provost walked outside to address the crowd, students threw snowballs at him before storming the building.

A three-and-a-half day sit-in ensued and did not end until administrators and student negotiators reached an agreement that, among other things, saved some programs and gave students a role in future decision-making processes, including a seat on the Board of Trustees.

Three years later in 1981, Robin Forman, now Emory’s Dean of the College, graduated with a Bachelor of Arts and a Masters Degree from that campus.

When Forman announced that Emory College and the Laney Graduate School would be eliminating or suspending departments and programs to reallocate resources, many students and faculty went on the offensive, objecting to a lack of due process and little, if any, transparency.

As many faculty voiced their surprise at the announcement, many Emory students shared similar frustrations with those students at UPenn who felt left out of a major University decision.

Thus the question remains: what role should college students play in major University decisions?

Rice University, 2010

When Forman became Dean of Undergraduates at the University of Rice in 2010, the university, like so many across the country, was in the midst of weathering the nation’s financial meltdown. That year the Rice Student Association formed the Budget Planning Committee to protect “highly valued programs” and represent “the interests of the student body to the Dean of Undergraduates and the Office of Finances on matters having to do with departmental budget planning,” according to a 2010 article in the Rice Thresher titled “Budget cut committee formed.”

In the article, Forman voiced support for the committee, noting that the Rice administration “has always strived to work with students when making decisions about the budget.”

“Student opinion has always played a central role in that process,” Forman said. “What this provides is a more systematic way that this communication takes place.”

The process, Forman said, was not only about using student input, but also keeping the student body informed.

“I’m always in favor of finding better and more efficient ways of sharing information with students and learning from the students of how to make Rice a better university,” Forman said.

Emory University, 2012

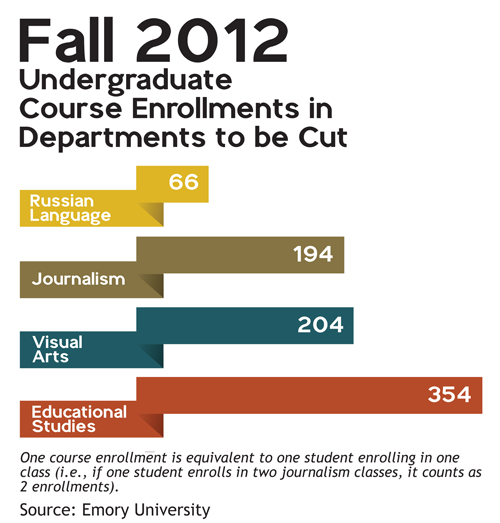

On whether Emory students should have played a part in the recent decision to eliminate or suspend a number of departments and programs, Forman said that students did play a role via enrollment numbers, which was one of the criteria in the decision-making process. Forman disagreed that students should have played a larger role.

“People’s lives and careers are at stake, and the fundamental principal is that those decisions should be guided by the faculty,” he said in an interview with the Wheel last Wednesday.

The sensitivity of the documents available to the Faculty Financial Advisory Committee as well as the four-year long commitment to the process also complicated student involvement, according to Forman. Those documents include department-planning materials, department self-evaluations, patterns of enrollment, course cross-listings with other departments and external reviews.

With regards to his time at Rice, Forman said that reaching out to the student body was easier since the campus is divided into 11 residential colleges composed of students from different academic fields. He would visit each residential college and hold some type of discussion or open forum where any student could participate.

“[At Rice], I came under some criticism for allowing the students too large a role in those budget cuts,” he said.

When Forman came to Emory, he said he met with student leaders and expressed concerns regarding decision-making processes.

“My sense of Emory was there wasn’t as much collaborative decision making as there needed to be in the College and that includes administrators, faculty, students,” he said.

Later, Forman elaborated, “I don’t feel like [Emory is] doing a good enough job, and I don’t feel like I’m doing a good enough job, and that’s independent of this particular decision.”

Forman said that he is “committed to this notion of shared governance and collaborative decision making.” Since he’s been at Emory, Forman said he has asked a number of student leaders how to recreate a system like Rice’s that incorporates disciplines from across the college.

“No one has given me any real sense of how that might happen,” he said.

Universities Across the Country

In addition to Rice University, Harvard University, Yale University, Columbia University, the University of Chicago and Stanford University are among the top colleges in the U.S. with official student-faculty committees or councils charged with advising various deans on matters that range from financial aid to undergraduate admissions to undergraduate curriculum.

Stanford University refers to its committees as “a very powerful instrument for allowing students’ voices to be heard at the administrative level,” according to its website.

Unlike many top universities across the country, there are no official student-faculty committees at Emory that work with the Dean of the College on matters relating to undergraduate education.

Forman said he meets regularly with College Council, the Student Government Association, student leaders, cultural groups, secret societies and other student organizations.

While there are no student-faculty committees that advise Forman, there are five student-faculty committees at Emory that cover a diverse range of topics: Academic Standards, Admission and Scholarships, Curriculum, Education Abroad and Educational Policy. The College Council is responsible for filling the three student seats on each committee.

Of those five committees, the Curriculum Committee comes the closest to governing undergraduate education, but Joanne Brzinski, senior associate dean for undergraduate education, said the committee was not included in the recent decision to eliminate or suspend several programs and departments. Brzinski reiterated Forman’s stance that the Faculty Financial Advisory Committee (FFAC) had access to sensitive documentation not appropriate for students and that the FFAC was created in 2008 for the purpose of dealing with major departmental decisions.

Brzinski said the Curriculum Committee is responsible for course approvals and for major and minor proposals. The committee was recently involved in the new credit-hours process and conducted a review of all interdisciplinary programs in the College.

The Process

Forman said he is not sure whether he would change anything about his process in light of the last two weeks.

“There are lots of possible ways to structure the decision-making process as well as the communication process,” he said. “It’s not hard to imagine alternatives, and I have to tell you for two years I’ve been questioning everything…Ultimately, I feel it’s not at all clear to me that there was a better process.”

Forman acknowledged the widespread confusion and anger across campus.

“Any process that leads to the decision to phase out three departments and organizations is going to lead to a significant amount of confusion and anguish,” he said. “The fact that that response happened does not in and of itself mean that there was a problem with the process.”

Forman went on to say that if the communication process were to stop now, then the process be inadequate.

Since this interview, Forman says he has met with College Council President Amitav Chakraborty to discuss creating a committee of students with which he could meet regularly.

– By Evan Mah

Contributed reporting by Arianna Skibell, Leon Kohl

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.

It’s VERY disturbing that the administration, and especially Dean Forman, continues to characterize the faculty and students’ justified shock and anger as “confusion”. No one is confused. Those individuals who have felt the cuts were unwise and unfounded have done more research and worked harder to disseminate the hard facts of the situation – the contributions of the faculty, the needs/desires of the students, and the true repercussions of the “restructuring” (firings) – than the administration has ever demonstrated. They’ve also been the only ones distributing the information in an attempt to inform the Emory and Atlanta community.

If anyone is confused, it is Forman and his friends in the administration. In comparing departments, they neglected to count foreign language publications as indices of scholarly productiveness, because they didn’t know they should specify that in their search engine. They have ignored the contributions of the DES because it didn’t fit their metric of “eminence”, which they themselves can’t even define. They think China is an important global force but forgot about India. And they don’t know how they are going to run the business school without the faculty in place to teach the requisite Econ courses. They are the confused ones – to call the student and faculty who are concerned and speaking out “confused” is manipulative, condescending, and the worst kind of politics.

Last thing to say here: if you went to the SGA meeting where Forman presented this plan (AFTER the announcement), you heard him describe Clint Eastwood as a “thought leader”. Enough said.