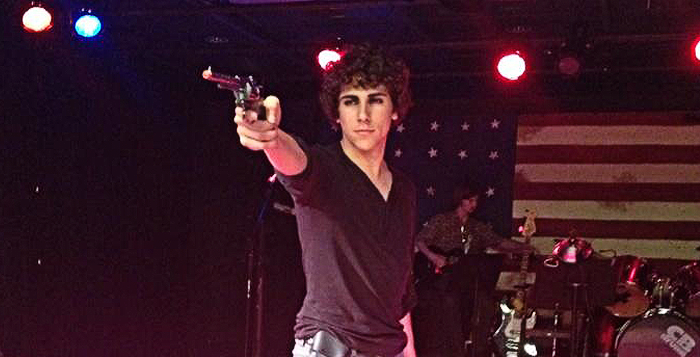

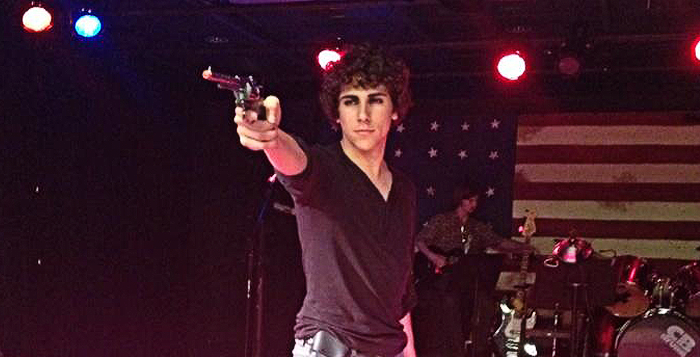

Courtesy of Tom Cassaro

College junior Tom Cassaro stars in AdHoc Productions’ Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, a rock musical about the life of President Andrew Jackson. The performance will run through next Sunday, April 20 at the Black Box Theater in the Burlington Road Building.

Of all the American presidents, who was the biggest rock star?

Probably not a question you ask too often. But that was precisely the topic of AdHoc Productions’ newest musical performance Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, which opened on Thursday, April 10 at the Black Box Theater in the Burlington Road Building and will run through next Sunday.

In case the title doesn’t give it away, Andrew Jackson is the rock star of the performance. And rock he does.

Played by College junior Tom Cassaro, Old Hickory sings, jams, fights and shouts his way to the top of the United States government.

Along the way, he falls in and out of love with his wife Rachel (College freshman Carys Meyer), tangles with the more “traditional” Washington politicians and completely screws over the American Indian tribes of the South.

But all in the name of working for “the people.”

The show explains that Andrew Jackson adopted his notorious hatred for American Indians after they made his childhood on the frontier difficult. Instead of fuming silently, he decides to become a leader so he can fume audibly and rid the country of the “horrors of the natives.”

In one particularly hilarious (and disturbing) scene, Jackson sits at a meeting with the chiefs of American Indian tribes, searching desperately for a way to get them off the frontier land. When they can’t reach a “mutually agreeable” situation, he jumps out of his chair and begins literally pushing the chief away.

“Can’t we talk about this rationally?” the chief asks, irritated.

“No!” Jackson shouts back, still pushing him.

In that way, most of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson is absorbed by the absurdity of this set-up.

Jackson wears tight jeans and guy-eyeliner, which is visually striking against the traditional 19th-century garb of the other characters.

The performers sing their way through political problems (“Populism, yeah, yeah!” chants the ensemble in the opening number).

And the staging itself harkens back to rock concerts of the 70s and 80s: one giant American flag spans the back wall, behind a band who spends the entire show onstage.

And as much as I’d like to say I know the exact meaning for all of these elements, I don’t.

But either way, it’s still just a really fun show.

The songs are just catchy enough and just ridiculous enough: particularly noteworthy are the narrative “The Corrupt Bargain” and the tragic but thoughtful “The Great Compromise.”

These numbers could have easily fallen into the trap of highlighting the outrageousness of these situations, but they ultimately serve as an opportunity to explain the motives of the characters and allow the audience to reflect on the larger implications of the show.

Not to say that they’re not laugh-out-loud entertaining: the political figures’ interactions always garnered a huge laugh, and Jackson’s no-nonsense, shoot-’em-up approach to all his problems were incredibly over-the-top.

“That’s right, motherfuckers! Jackson’s back!” he shouts, in the midst of a musical number.

Each role was cast perfectly, in such a way that no one role really outshone the others. Cassaro was just absurd enough and just sensitive enough to pull off the role of Jackson.

College sophomore Josh Young was, as always, deadpan hilarious, as the pot-bellied Martin Van Buren who ultimately becomes Jackson’s headset-wearing assistant. (“Tell the Indians to get lost!” Jackson cries. Running offstage, Young mumbles into his headset, “Get lost, Indians.”)

And College junior Julia Weeks was enchanting as both Jackson’s silently menacing friend-turned-foe Chief Black Fox and the squirrel-carrying, politically-ambitious Henry Clay.

One final aspect of the show which deserves exceptional credit is the choreography.

College junior Aneyn O’Grady contributed to the steps, which served as the perfect complement to the entertaining, melodic songs.

Through O’Grady’s tight yet buoyant movement, the ensemble members managed to be engaging to watch on their own but not so overwhelming that they detracted from the enjoyment of the songs themselves.

As far as understanding the overarching meaning for this rock concert of a political story, the closest we got for that was one of the final lines of the show.

“Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson” winds down as Jackson realizes his political career isn’t going to be quite as straightforward as he had hoped (“They can’t stop me from doing what I know the people want!”), and the storyteller (College junior Chelsea Walton) explains that though Andrew Jackson was pretty popular at the time of his presidency, history has recently begun to question whether he was, in fact, “a people’s president, or just a genocidal murderer.”

At that, Jackson cries, “Fuck history!”

The storyteller looks at him skeptically and calmly responds, “You can’t shoot history in the neck.”

And maybe that was the whole point of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson.

He fought his way to the top, pretty much killing anyone who got in his way – but that method of facing his problems wouldn’t help him change how history perceived him.

Or maybe the whole point was just to have a fun rock show.

And given the laughs, music and story that it provided, that explanation is also just fine by me.

– By Emelia Fredlick

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.