In 2010, I went with my parents to Luna Park in Coney Island – more specifically, directly next to the timeless Luna Park – to see the short season Single A minor league Brooklyn Cyclones play the Staten Island Yankees. Before the game, my father and I watched as the Staten Island shortstop, a compact, limber kid too young to shave, took ground balls and we listened as the pounding of his throws into the equally young first baseman’s mitt echoed off the waves crashing just outside the center field wall. I turned to my father, “I feel bad for him.” No explanation was necessary. If this kid, probably still living in euphoria of his signing bonus, made it to the Majors, he’d be behind Derek Jeter.

On Wednesday, Feb. 12, Jeter announced via Facebook that he will retire after the 2014 season. This past year, the now 39-year-old Jeter, once a kid from Kalamazoo, Mich. who told everyone he met that he was going to play shortstop for the Yankees, showed for the first time that he was in fact a mere human. Reoccurring leg and ankle injuries kept his total games played to 17 and in that small sample size, the .312 lifetime hitter hit a Mendoza line .190.

Since Jeter’s 1996 Rookie of the Year season, the Yankees have won five World Series’. To put that number in perspective, if the Yankees only existed since that year, they would still be in the top 50th percentile of MLB teams in total World Series wins.

Jeter is one of the best clutch players of all time, with a nickname of Mr. November and 20 home runs and a .308 batting average in post season play. He is already the all-time Yankees leader in hits with 3,316, at-bats with 10,614, games with 2,602 and stolen bases with 348.

In any year during that time period, however, if you had asked anyone who the best player in baseball was, there would have been a slim chance they’d say “Derek Jeter.” In the late 1990’s, you’d hear “McGwire” or “Sosa.” At the turn of the century, you’d get “Giambi” or “A-Rod.” Today, it’s “Miguel Cabrera.”

But not being on the cover of Sports Illustrated every year is part of what comes with being the most honorable and pure athlete in your sport.

The Steinbrenner’s preach “Pride in Pinstripes.” They even made Johnny Damon shave his beard and cut his hair when he signed. But the Bronx Bombers often end up a team of mercenaries. A-Rod was bought from the Rangers, Granderson stolen from the Tigers, Teixeira taken from the Braves.

Jeter has been in the Yankees’ franchise since he was drafted sixth overall in the 1992 draft. Cano, the only lifetime Yankee star last season left for more money with Seattle in December.

Jeter may have said last year that he’d be open to offers from other teams, but he will retire as he was born in baseball: as a Yankee.

That security Jeter gave fans, however, kept him out of the spotlight. When Jimmy Rollins predicted in 2009 that the Phillies would beat the Yankees in five World Series games, Jeter was confident, but quiet.

Then again, maybe Jeter simply wasn’t the everyman’s player. Throughout the biggest power surge in baseball history, he never had a season with over 24 home runs or 102 RBIs.

He’s almost a connoisseur’s player. Supposedly, Ty Cobb didn’t believe in the sort of baseball that came with Babe Ruth. He believed in slapping a single, stealing second, and scoring on the next batter’s single. According to Charles C. Alexander’s biography of Cobb, the outfielder, outraged at hype over Ruth’s power, told a sports writer, “I’ll show you something today. I’m going for home runs for the first time in my career.” Cobb then proceeded to go 6-6 on the day with three home runs, a double and two singles.

Don’t get me wrong, Jeter has some pop. But he is not a power hitter. He is a guy who gets on base and moves around. He plays the way Cobb played – minus the high-spike slides.

When powerhouses McGwire, Sosa, Bonds and Giambi were accused of steroid use almost 10 years ago, fans felt cheated by their former heroes. The 2007 Mitchell Report only made matters worse. It may have kept Jeter off a few Top 10 lists, but being a Hall of Fame caliber player who was a contact hitter gave fans a glimmer of hope that nobility still existed in the sport.

And he has five Gold Gloves too.

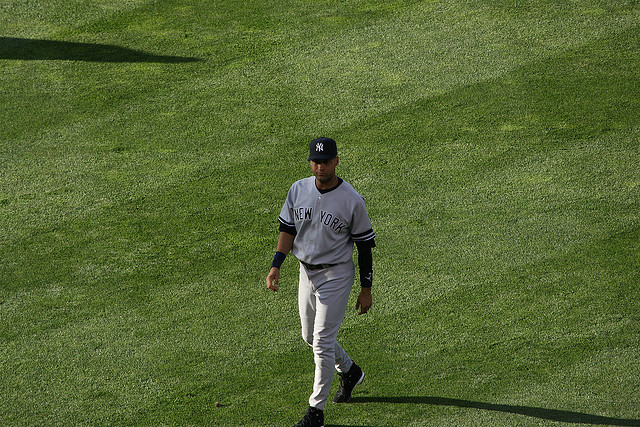

In high school, he was getting clocked at 90 mph. from shortstop. That unequaled arm strength is at no time more event than when he makes his infamous leaping throw.

When a ball is hit towards third base, a shortstop often doesn’t have time to square around it and must backhand it. With his left foot pointed towards third, his right pivoted, his back facing first base and his feet reset before he can throw.

When Jeter has to backhand a ball, he leaps in the air, simultaneously twisting his torso toward first base, and throws while still in the air, miraculously making the throw on a perfect line.

His retirement statement was not bitter. Realizing that his body is aging exponentially, he said, “The one thing I always said to myself was that when baseball started to feel more like a job, it would be time to move forward.”

Nonetheless, it’s tough to see a player like Jeter age and retire, because he’s seemed like more than an athlete. You expected him to always be there. He’s been a role model, a remnant of class in professional sport and a guy who always seemed to find a way to win and win with pride.

This retirement announcement, however, is yet another reason we ought to commend Jeter. Referring to his dream to play shortstop for the Yankees, he said, “It started as an empty canvas more than 20 years ago, and now that I look at it, it’s almost complete … Now it is time for the next chapter. I have new dreams and aspirations, and I want new challenges. ”

I, for one, an eager to see what the Yankee captain will do next.

– By Zak Hudak

The Emory Wheel was founded in 1919 and is currently the only independent, student-run newspaper of Emory University. The Wheel publishes weekly on Wednesdays during the academic year, except during University holidays and scheduled publication intermissions.

The Wheel is financially and editorially independent from the University. All of its content is generated by the Wheel’s more than 100 student staff members and contributing writers, and its printing costs are covered by profits from self-generated advertising sales.